The Largo of Act II, Scene 3, is the central scene of the central act of Berg’s Wozzeck. It is during this scene that Wozzeck confronts Marie about her affair with the Drum Major, the image of the knife is crystallized, and the fate of the two main characters is effectively sealed. That these crucial events take place at the very center of the opera is not simply coincidental. Rather, Berg calls attention to their centrality with careful recollection of previous musical ideas, foreshadowing of future scenes, and symmetrical distribution of musical material on either side of the scene.

[A complete list of illustrations and thumbnails appears at the bottom of this post.]

A broad overview of the Largo shows that Berg incorporates a number of different musical techniques to support the dramatic action and underlying psychological drama, the most obvious of which in this scene is instrumentation. The smaller, more intimate, forces of the chamber orchestra (the exact instrumentation of which is borrowed from Schoenberg’s Kammersymphonie, Op. 9) are an appropriate analog for a confrontation seemingly between two lovers. And for Wozzeck, the moment is actually about his relationship with Marie alone, and her betrayal of him. It is therefore fitting that Berg begins the scene with chamber orchestra scoring, and continues to use this smaller group to accompany Wozzeck’s questioning of Marie’s loyalty to him. But Marie, in her own mind and through consummation of her new relationship with the Drum-major, has already left Wozzeck, and when she replies to Wozzeck’s accusation her dialog is accompanied by the remaining full orchestra. As the scene progresses, and as Wozzeck realizes that he has lost Marie, the distinction between chamber and full orchestra becomes less and less distinct. The orchestration therefore works as a metaphor for the intimacy that once existed between Wozzeck and Marie and its ultimate diffusion.

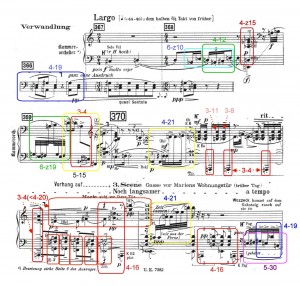

Like the other scenes in the opera, the Largo is enclosed between short orchestral passages within which are contained the main thematic and harmonic material of the scene itself. The main Largo theme is introduced by the solo cello in mm. 367-9 (see Illustration 1: Orchestral interlude, main themes and set-classes, mm. 366-73). The theme consists of two segments, the first of which is set 6-z10, m. 368, and the second, set 6-z19. The latter of these sets is familiar throughout the opera as part of the Wozzeck-Marie set complex (6-z19/6-z44), while the former 6-z10 is significant to the Largo alone.1 But the two sets share a 5 note sub-set, 5-16, and therefore sound quite closely related. In the context of the scene, one can be thought of as a clear variation of the other, especially given their similar rhythmic motion and contour.

Several other familiar motives appear in the opening interlude:2 the Drum-major’s “Fanfare” motive, mm. 370 and 373, as set-class 4-12; “Marie’s aimless waiting” motive, m. 372, as set-class 4-16 (a variation of the original 4-20 version, which replaces an IC5 with an IC6); “Wozzeck’s entrance”, m. 373, as set-class 5-30 (a sub-set of 4-19); a “Wozzeck’s hallucination” motive, m. 369, as set-class 5-15. One additional set-class, 3-4, does not have particular significance in the opera as a whole but appears throughout the Largo, particularly in reference to Marie, as it is a sub-set of set-class 4-16. All of these motives and their set-classes serve as a reintroduction to material that will make up the bulk of the scene proper, and that will guide us through the meaning of the text and the characters’ underlying thoughts and emotions.

At the center of the whole scene is the “Knife” motive, a chromatically converging idea which is clearly distinct from the other main melodic and harmonic material of the scene. Within this central “mirror”, the images of the surrounding interludes are reflected: The passage in mm. 363-6 (Illustration 2: Orchestral interlude, pitch-classes of melodic approach to 4-19 ostinato, mm. 362-8) reappears in near-retrograde in mm. 408-11 (Illustration 3: Orchestral interlude, pitch-classes of melodic departure from 4-19 ostinato, mm. 406-11); and the main Largo theme of mm. 369-70, which is introduced following the 4-19 “Wir arme Leut” set-class ostinato, later brings about the ostinato’s return in mm. 402-6. That set-class 4-19 is “reflected” in the knife motive is significant because the tragic fate of Marie and Wozzeck is directly related to their poverty.

The most literal use of set-class/motivic reference occurs first at m. 373, with “Wozzeck’s entrance” set 5-30 used literally to introduce Wozzeck onto the stage. But there are other, more subtle references to the plot of the Largo that are suggested by these motives’ appearances in the interlude. “Marie’s aimless waiting” in m. 372 refers locally to her standing at the door, waiting for something (of which she is not aware yet) or someone. This someone of course turns out to be Wozzeck, but one does have the underlying sense that she is hoping for the Drum-major. This sense is further confirmed by the “Fanfare” motive of mm. 370 and 373, and by a loosely inverted statement of the military march music in m. 371. Berg even gives a premonition of the “Knife” through a series of descending chromatic 3-4 (a set associated with Marie) chords in m. 372, having blossomed out of the military idea from the previous measure. In this short moment of music, one could argue that Berg has summed up the events of the opera up to that point through leitmotivic and set-class association: Wozzeck’s (and Marie’s) poverty as the root of their dire circumstances; the appearance of the Drum-major at the march in Act I; his connection to Marie; her waiting; and, what will ultimately follow, her death at the hands of Wozzeck’s knife.

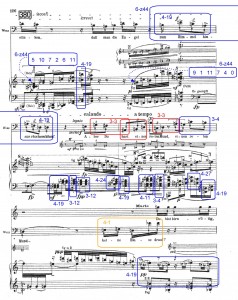

As the dialog between Marie and Wozzeck begins (m. 374) the meaning of the harmonic language becomes even more subtle (see Illustration 4: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 374-9). Marie’s first line, “Guten Tag, Franz”, not surprisingly features set 4-18, one that is associated with her throughout the opera. More interesting is Wozzeck’s use of the same set, and with the same melodic contour, in m. 378, when he asks “Bist Du’s noch, Marie?” (Is it still you, Marie?), as if to suggest his unwillingness to equate the once-trusted Marie with the now unfaithful one. This desire to deny reality is also apparent in Wozzeck’s lines in mm. 375-6, where he exclaims “Ich seh’ nichts. . .” (I see nothing). Because his sprechstimme in the passage is bounded by set-class 3-8, a whole-tone sub-set which represents the idea of “fitting in” in the harmony of the opera, we understand that Wozzeck is not yet willing to see how everything fits together. While he knows from the other characters in the opera that Marie has been unfaithful, he refuses to believe in its truth.

Berg also alludes to the overall idea of confrontation between Marie and Wozzeck by assigning Marie-related sets 4-16 and 4-18 to the accompaniment throughout this first passage which consists primarily of Wozzeck’s spoken dialog. Hence, the dialog or argument between Wozzeck and Marie is taking place even when only one of them is speaking.

In the midst of this complex harmonic framework, Berg continues to present the main theme of the Largo as a counter-melody, in mm. 377-8, and elsewhere. The 6-z19 theme becomes a logical transition into the melodic statements of its complementary 6-z44 in m. 380 (see Illustration 5: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 380-3). Here we find the moment cited by Perle in “Berg’s Master Array” in which each of the independent voice-leading strands, save the highest, follows an ascending pattern of a single repeated interval. Perle described this as a manifestation of the “misfit” idea, where all the lower voices fit the array and only one (representing Wozzeck) does not fit in.3 Taken by itself, this upper line is set-class 6-z44, which we associate with Wozzeck and Marie’s union. It may therefore be even more accurate to say that this moment represents the idea that it is Wozzeck and Marie that don’t fit together. Above this accompaniment, Wozzeck describes Marie’s sin as “able to smoke the angels out of heaven” in a descending 6-z44 line, conveying an image of Wozzeck’s and/or Marie’s ultimate descent out of heaven and into hell.

The passage beginning around m. 390 features a wonderful juxtaposition of musical ideas which clarify the true meaning of the text (see Illustration 7: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 390-2; sets in blue represent Wozzeck, sets in red represent Marie). In response to Wozzeck’s angry question about where the Drum-major once stood with Marie, she replies, “Since the day is long and the world is old, lots of people can stand in one place. . .” That she is humoring, even mocking, Wozzeck is most apparent when we notice that her accompaniment is constructed of alternating set-classes 4-18 and 4-16, both of which Berg associates with Marie, placed above a G-natural/D-natural pedal-point, the pitch-class pair Berg associates with Marie’s relationship with the Drum-major. Hence, even as she is speaking with Wozzeck, and though he knows of her unfaithfulness, she continues to lie to him, or is perhaps at that very moment thinking of the Drum-major.

Marie is certainly thinking of the Drum-major as she claims, “You can see lots of things, if you have two eyes, and aren’t blind, and the sun is shining.” The allusion to the Drum-major is here sung by Marie at the end of m. 392, on the words “Man kann viel seh’n. . .” with a melody lifted from Act I, Scene 3, m. 345, in which Marie sings “Soldiers are a splendid sight.” In the latter case, the set-class of the motif is 4-2, an almost-whole-tone set, and therefore the pitches are slightly different from the Act I version, but the melodic contour, rhythm, and pitch similarity are unmistakable.

Also in m. 392 Berg makes a clear reference to the Drum-major with the military march motive accompanying Wozzeck’s line “Ich hab ihn ge-seh’n!” (I saw him!). That “him” refers to the Drum-major is clear enough even without the military music, but it is worth noting that the theme is somewhat harmonically developed from its first non-inverted appearance (of this scene) at m. 388. By the latter statement, the texture of the motive has grown into four- and five-voice chords, based on set-class 4-20 (“Marie’s waiting”). Wozzeck is more and more able to accept that Marie was unfaithful to him, and thus the march music appears in a more formidable texture.

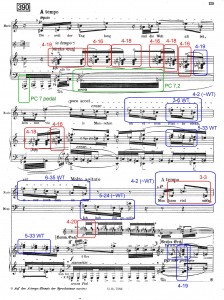

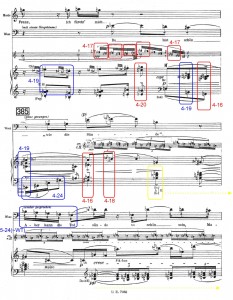

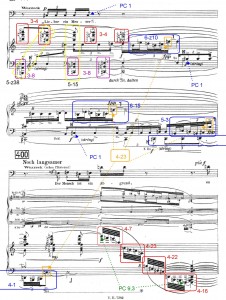

The focal point of the scene, and of the opera as a whole, begins in m. 395 and continues through m. 400 (see Illustration 8: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 395-7; sets in red represent Marie or Marie with child, sets in green represent the doctor, sets in yellow represent Wozzeck’s hallucination, sets in orange and purple represent the knife). Within this short passage is a thick and very complex interwoven series of musical ideas, all of which bring to light the ultimate fate of Marie at the hands of Wozzeck. The passage begins with Marie’s impassioned “Rühr’ mich nicht an” (Leave me alone) as a reaction to Wozzeck’s motion to strike her. This is of course the same utterance she made in response to the Drum-major’s “unwelcome” advance in Act I, sung (or, rather, spoken) at the same pitch level, and with the same rhythm. The function of this phrase is somewhat akin to a parola scenica, in that it marks with unmistakable clarity a dramatic culmination. That Marie uses the same phrase in her dealings with both the Drum-major and Wozzeck underlies the intertwined fates and relationships of the main characters in the opera.

Directly following Marie’s exclamation is the “Knife” motive, here in its most clear and first complete appearance, played by descending solo tremolo strings. When one considers, as mentioned above, that Wozzeck is identified primarily with the chamber orchestra in this scene, then the orchestration of the “Knife” becomes significant: it is the only point at which the chamber instruments accompany Marie. Here, then, we envision the chamber orchestra as Wozzeck’s own hands holding the knife that ultimately will take Marie’s life.

The motive itself has two main harmonic and melodic characteristics: the convergent chromatic motion, and the three-note sets that make up the convergent harmonies. In the knife’s first instance at m. 395, these sets are 3-5 descending and 3-8 ascending. The resultant five- and six-note chords created by their vertical overlapping are, among others, 6-z28 and 5-19. Set-class 6-z28 is a set that Berg normally associates with Marie and her child, and except for the fact that this set appears at the beginning and end of the motive, there is perhaps little evidence to support the idea that the child has a role in this passage (except for the obvious fact that his fate is on some fundamental level tied to that of his parents—but to go down this road would be to call into question the child’s relationship to every event involving his parents). But the other of these sets, 5-19, does seem to take on a level of importance within the knife motive, as it is a set that Berg associates with Wozzeck’s hallucinations. From this point through the end of the scene, we begin to see a significant number of sets related to the hallucinations (including set-class 5-15). These hallucinations are likely Wozzeck’s imagining Marie’s murder, an idea that coincides with the knife motive and continues to build in intensity the more Wozzeck ponders it.

At the same time, it is Marie herself who brings about the very idea of the knife when she says “Lieber ein Messer. . .” And from the moment she utters those words, Berg shows that she has, willingly or unwillingly, submitted to her fate, by setting her text to the note C-sharp, the pitch-class that signifies submission throughout the opera (see Act I, Scene 1, where Wozzeck continually submits, “Yes, Captain” on PC1). Only moments later, in m. 399, Wozzeck has similarly submitted to the eventual murder of Marie, repeating her words “’Lieber ein Messer’. . .” on the same PC1 (see Illustration 9: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 398-400; sets in blue show the Largo theme, sets in red represent Marie, sets in yellow represent Wozzeck’s hallucination).

There is a curious variation in the set-classes of the knife motive when it appears in mm. 397-8: Where the upper portion was originally set-class 3-5, it is here transformed into 3-4. One cannot help but wonder if this is of some dramatic importance. Since set-class 3-4 is associated with Marie throughout this scene in particular, perhaps this is Berg’s subtle representation of the knife’s and Marie’s coming together. Even so, it seems difficult to imagine that the change could be heard in the context of the performance given the highly chromatic nature of the motive itself.

The passage beginning around m. 400 is the beginning of the end of the scene, and in a broader sense of the opera itself (see Illustration 9: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 398-400; sets in blue show the Largo theme, sets in red represent Marie, sets in yellow represent Wozzeck’s hallucination). Berg begins to return to the main thematic melodies of the Largo, and at their original pitch level, rounding out the symmetrical structure of the scene. The portion of the theme that happens first in m. 368 as set-class 6-z10 also comes back as that same set, but continues to branch off into incarnations of the same melody with slight pitch variations. This happens twice in m. 399 as set-classes 6-15 and 5-3, and in truncated form in m. 399-400 as set-class 4-1. These last set-classes don’t have any particular significance on their own, but the specific final pitches added to the original 6-z10 form may: Taken together, they form set-class 4-23, the perfect fourth chord that is so often identified with the Drum-major. As is the case with the variation of the knife motive, this may not be of particular significance, but nonetheless it is a collection of pitches that is made clearly audible through careful orchestration and registration.

Berg uses a series of rapid ascending and descending textures to paint a picture of a dizzying abyss following Wozzeck’s “Der Mensch ist ein Abgrund”. In the piano reduction, the abyss consists of mostly Marie-related four-note sets, 4-23, 4-22, and 4-16, with the additional 4-7. In the full score, the set construction is quite different, with individual instrumental parts consisting of their own set-class structures, each of which has some dramatic significance on its own (see Illustration 10). Of particularly obvious importance: the flute, E-flat clarinet, and A clarinet parts feature set-class 3-5, one of the knife motive sets, bounded by set-class 3-3, a “Kind” set; and the viola centers on set-class 5-35, a super-set of the fourths-chord 4-23, associated with the Drum-major, bounded by 5-21, a “Marie as mother” set. In this context, one has the sense that the child’s fate is represented as locked up by the transgressions of his mother and the Drum-major.

In both the condensed and full score versions of the “abyss” passage, the upper and lower bounds are the same: E-flat on the low end, and A-natural above. In the most local context, this tri-tone comes from the set-class 4-16 “Marie’s waiting” motive of m. 372. There may well be significance in this particular tri-tone for Berg beyond this scene, and even this opera, according to Pat Bamford-Milroy. In his article about Berg’s real-life affair with a woman named Marie and their child Albine Scheuchl, Milroy shows that at the ends of the three acts of the opera (he does not make mention of the individual scenes), Berg makes reference to his daughter’s initials as pitch representations (A-natural and E-flat are “A” and “S” in the German transliteration).4 As Berg was a young, and unmarried, man at the time of his relationship with Marie, he had no relationship with his daughter as she grew up, and only later developed a very cursory relationship with her. Perhaps his injection of her name into his work was a reflection of his empathy with his work’s characters, or maybe it was simply a tribute. In the context of the opera, it seems plausible that there is some connection between the use of these particular pitches in conjunction with a passage that includes so many “Kind” related sets.

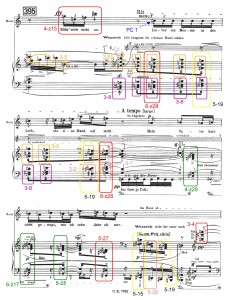

As mentioned above, the interlude following Scene 3 of Act II contains the material from the opening orchestral passage. When it does return, it is affected by the dramatic events of the scene, and therefore exhibits signs of subtle variation (see Illustration 11: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 402-11, including orchestral interlude; sets in blue represent Wozzeck, yellow represents Wozzeck’s hallucination). Most notably: the chamber orchestra concept has given way to the full orchestra, and the ideas that were initially presented by the solo cello are now played by the full string section; a pedal-point on F-sharp accompanies the passage; and the inverted version of the military march motive, which we heard first in m. 371, is expanded to included four-note chords, the result of which is Wozzeck’s set-class 4-19. This last point is significant, since it shows that after having confronted Marie about her affair with the Drum-major, Wozzeck is fully aware of her disloyalty.

The F-sharp pedal-point has one primary function: to serve as a leading tone into the upcoming Langsammer Ländler passage in G (minor). One can call the passage beginning around m. 414 in G minor only in the loosest sense, since most of the functional harmonies are overlaid with different, sometimes functionally contrasting harmonies from the same key or from a parallel mode (see Illustration 12: Orchestral interlude, mm. 414-25, general harmonic analysis; sets in yellow, 3-9 and 5-z18, represent Drum-major). Schmalfeldt describes this section as the juxtaposition of G minor and E-flat major tonalities.5 Berg himself, in a lecture on the opera, described his use of “polytonality” as representative of “harmonically primitive” music,6 and one might assume that tavern music might likely be just such music. However, to call this passage “polytonal” seems to be stretching the meaning of polytonality, since the overall sense of the central pitch is always G-natural. It might suffice to describe the passage as two separate harmonic strands, both in the same “key”, but each one slightly misaligned with the other.

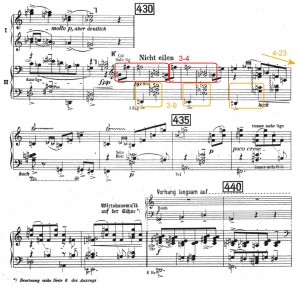

Regardless of the tonality, the Langsammer Ländler music is strongly characterized by an abundance of perfect-fourth sets, which are normally associated with the Drum-major, and here serve to introduce him at the beginning of Scene 4. Even the short passage beginning at m. 430 (Illustration 13: Orchestral interlude, mm. 428-40; Drum-major sets) consists of a combination of set-classes 3-9 and 3-4, in combination to form 5-35, another Drum-major set-class.

When the opera Wozzeck made its debut, and for considerable time afterward, a great deal of emphasis, and even a fair amount of criticism, was levied upon Berg’s use of so-called “classical” formal structures within the work. As this scene is simply a portion of what Berg thought of as a larger five-section symphonic form, and since this paper deals almost exclusively with only the music from this scene, it is difficult to draw conclusions with respect to the larger form and how it might fit in. However, Berg himself commented on the questions as to whether or not it was reasonable to inject such forms into an operatic work:

No one in the audience, no matter how aware he might be of the musical forms contained in the framework of the opera, of the precision and logic with which it has been worked out . . . pays any attention to the various fugues, inventions, suites, sonata movements, variations, and passacaglias about which so much has been written.7

It seems, according to what Berg claims, that if the audience does not necessarily perceive these formal structures, then there would have to be other, more apparent means of organizing musical material. Based on this notion, it becomes even more evident that set-class associations not only inform the underlying dramatic meaning, but also the basic structure of the piece. In particular, the Largo, which unlike a passacaglia or sonata has no inherent formal guidelines, relies almost exclusively on the continuity of harmonic language.

Illustration 6: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 384-6; sets in blue represent Wozzeck, sets in red represent Marie—with the exception of 4-17 which relates to both Marie’s relationship with her child and Wozzeck’s stupidity

Illustration 9: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 398-400; sets in blue show the Largo theme, sets in red represent Marie, sets in yellow represent Wozzeck’s hallucination

Illustration 10: Act II, Scene 3, m. 401, “Abyss” image; sets in red represent Marie, sets in orange represent child, set in purple represents Drum-major

Illustration 11: Act II, Scene 3, mm. 402-11, including orchestral interlude; sets in blue represent Wozzeck, yellow represents Wozzeck’s hallucination

Illustration 12: Orchestral interlude, mm. 414-25, general harmonic analysis; sets in yellow, 3-9 and 5-z18, represent Drum-major

Bibliography:

Berg, Alban. “A Word about Wozzeck.” in Douglas Jarman, Alban Berg: “Wozzeck”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Berg, Alban. “A Lecture on Wozzeck.” in Douglas Jarman, Alban Berg: “Wozzeck”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Perle, George. The Operas of Alban Berg, Volume One/Wozzeck. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

Perle, George. “Berg’s Master Array of the Interval Cycles.” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Jan., 1977): 1-30.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. Berg’s Wozzeck: Harmonic Language and Dramatic Design. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

Bamford-Milroy, Pat. “Alban Berg and Albine Wittula: Fleisch und Blut.” The Musical Times, Vol. 143, No. 1881 (Winter, 2002): 57-62.

1The set-class complex 6-z19/6-z44 appears in Janet Schmalfeldt’s detailed analysis of Wozzeck as a whole. Her work is the first major published account to categorize much of the opera’s harmonic language in set-class terms. However, George Perle’s Operas of Alban Berg, v. 1, includes much of the same identification of primary harmonic material using a different system.

2Throughout this analysis, the familiar names for the various leitmotifs are from indications in the score and from analyses by both George Perle and, later, Janet Schmalfeldt.

3George Perle, “Berg’s Master Array of the Interval Cycles,” The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Jan., 1977), 1-30.

4Pat Bamford-Milroy, “Alban Berg and Albine Wittula: Fleisch und Blut,” The Musical Times, Vol. 143, No. 1881 (Winter, 2002), 57-62.

5Janet Schmalfeldt, Berg’s Wozzeck, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 63.

6Alban Berg, “A Lecture on Wozzeck,” in Douglas Jarman, Alban Berg: “Wozzeck”, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 161.

7Alban Berg, “A Word about Wozzeck”, in Jarman, 153.

?